|

|

Bio Dr. Beca is a vitreoretinal surgeon at Wills Eye Hospital/Mid-Atlantic Retina in the Philadelphia region. He has no disclosures to report. |

A 27-year-old female initially presented to the emergency room with three months of photophobia, tinnitus, hearing loss and headaches.

Workup and imaging

Visual acuity was 20/25 in the right and left eye. Exam showed 2+ anterior chamber cell with mild anterior vitreous spillover, as well as disc edema in both eyes. Although idiopathic intracranial hypertension was suspected based on the confluence of symptoms, body habitus and demographics, the concurrent bilateral anterior uveitis prompted a thorough workup which included neuroimaging, lumbar puncture and broad infectious inflammatory laboratory workup which were all consistent with IIH alone.

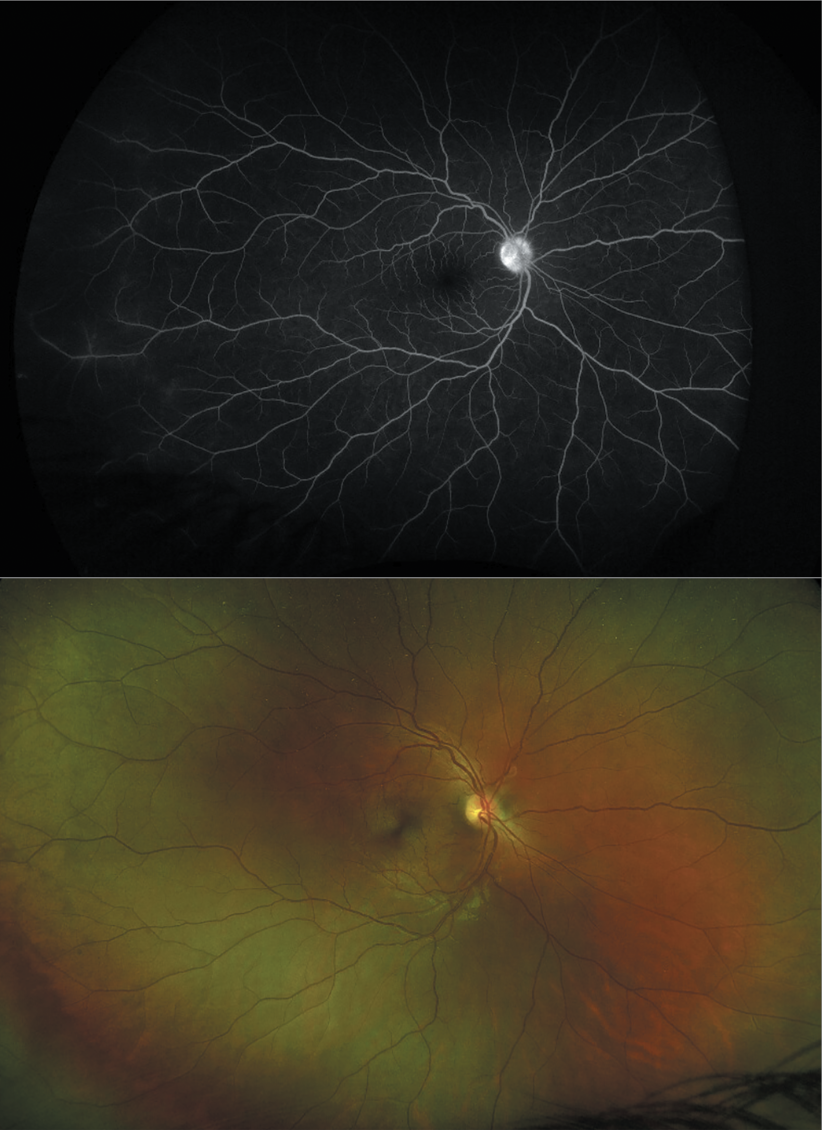

The patient was referred to the retina clinic where multimodal imaging, which included spectral domain macular OCT, fundus autofluorescence and fluorescein angiogram were unremarkable excepting mild disc leakage in the late phase angiogram (Figure 1). The anterior uveitis was successfully treated with topical steroids and subsequent taper, while the patient saw neuro-ophthalmology for the management of the concurrent IIH with oral acetazolamide and weight loss.

|

|

Figure 1. Patient fundus photo with mild optic disc edema and unremarkable fluorescein angiogram at initial presentation. |

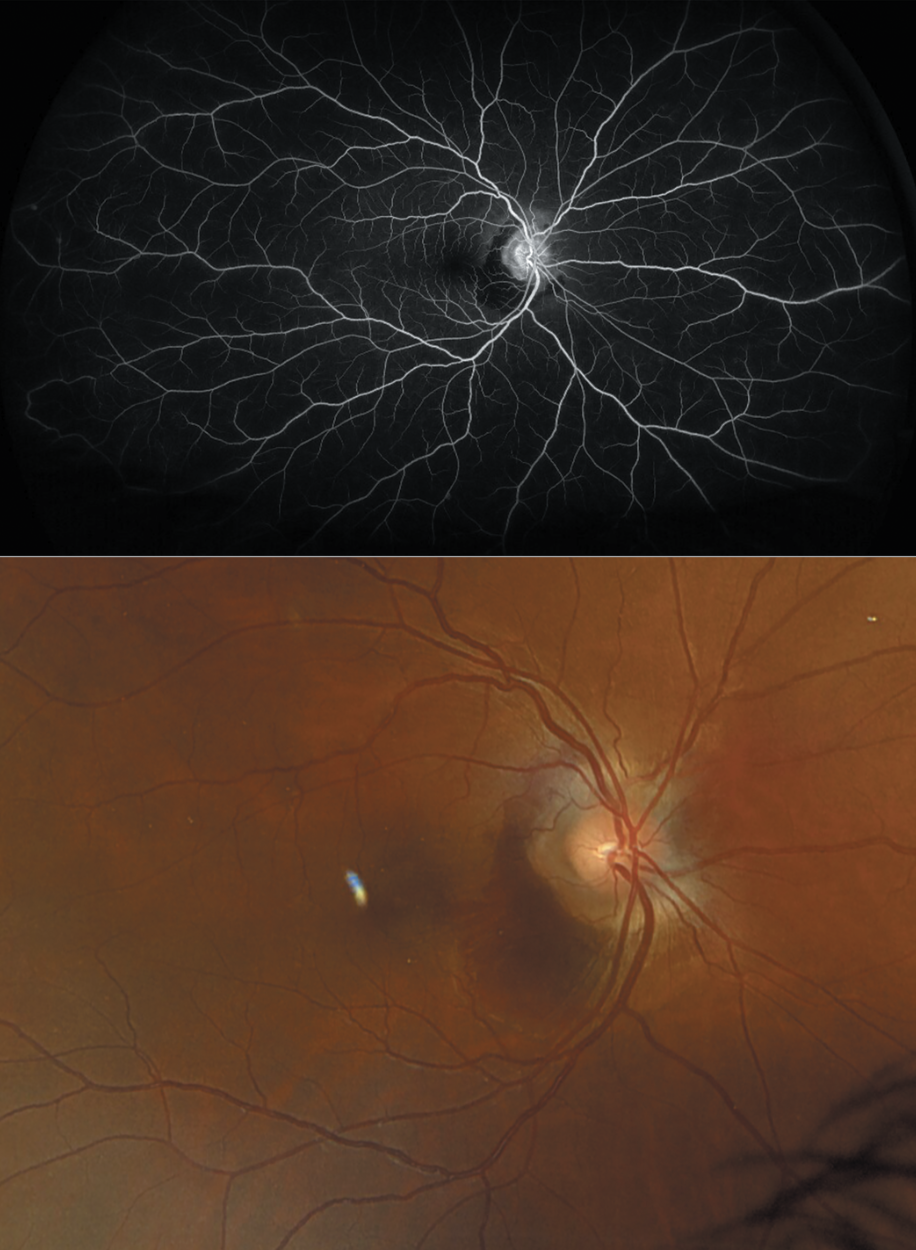

The patient then presented nearly four months later with new sudden painless vision loss in the right eye. At this time vision was 20/50 in the affected eye and examination revealed a peripapillary subretinal hemorrhage and again bilateral anterior chamber cell but no evidence of posterior inflammation. A peripapillary macular neovascular membrane and secondary hemorrhage was suspected, likely in the setting of chronic IIH, an uncommon though well-established entity (Figure 2). However, upon further review of symptoms, the patient acknowledged having “itchy and raised” rash within several of her tattoos reported as chronic for the preceding six months, corresponding with the time of the original symptom onset (Figure 4).

|

| Figure 2. Fluorescein angiogram is once again unremarkable beyond the MNV and blockage by the subretinal hemorrhage (top). The fundus photo taken at second presentation depicts peripapillary MNV with subretinal hemorrhage. |

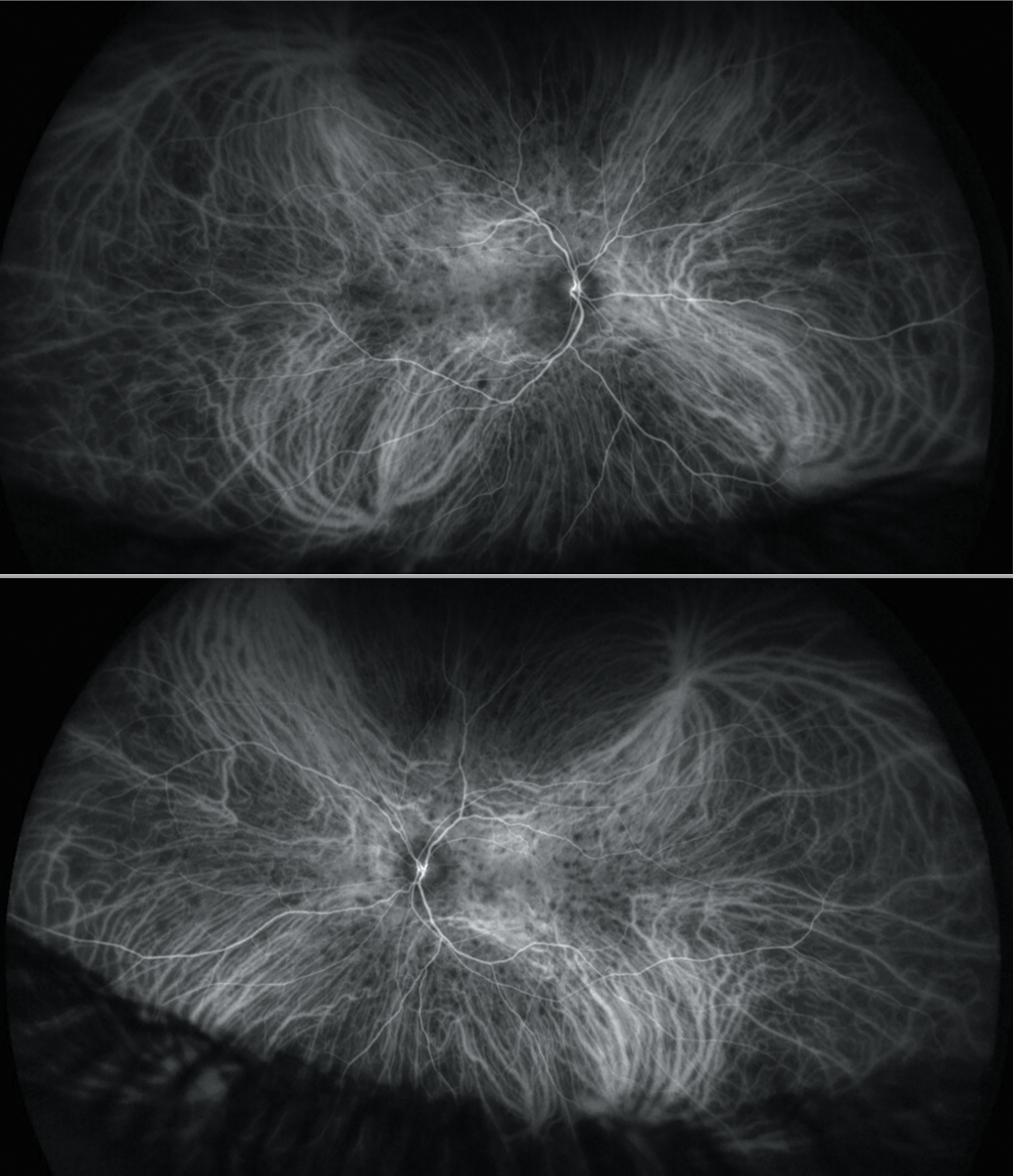

Repeat multimodal imaging was performed, this time including indocyanine-green angiogram. The FA confirmed the MNV but once again showed no vasculitis or disc leakage (Figure 2). However, the ICG angiogram revealed bilateral scattered small hypofluorescent lesions consistent with choroidal granulomas as are often seen in patients with sarcoid uveitis or tattoo- associated uveitis (Figure 3).

The patient was treated with a single bevacizumab intravitreal injection as well as 60 mg of oral prednisone with a subsequent taper. Treatment resulted in improvement in vision and apparent resolution of the MNV and subretinal hemorrhage with vision improving to 20/25 in the right eye and the pruritic tattoo rash. Notably, once the oral steroids were tapered off, the patient developed recurrence of anterior chamber cell as well as the pruritic rash. At this point the patient was referred to rheumatology to initiate systemic immunosuppression.

|

|

Figure 3. Patient ICG angiogram depicts bilateral scattered hypofluorescent choroidal lesions consistent with sarcoid granulomas. |

Discussion

Peripapillary neovascular membranes can occur in a wide variety of conditions. In a large retrospective series of over 1,100 cases, only six developed peripapillary MNVs. Although rare, MNVs can occur in patients with IIH and reported treatment approaches include observation, management of the IIH, and anti-VEGF injections.1,2,3 Unlike other MNVs, most reports in the literature suggest that once treated and the underlying condition is controlled, the MNVs don’t recur.1

|

| Figure 4. Patient tattoos depict an elevated and symptomatically pruritic rash localized to the darkly pigmented tattoos. |

In the setting of chronic uveitis, secondary MNVs occur rarely (~2 percent) but can be suspected in the setting of just about any cause of chronic inflammation.1,2 Among causes of infectious uveitis, ocular histoplasmosis is the most common entity where MNVs, including peripapillary MNVs, are common. In addition, toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis and West Nile Virus are infrequent causes (all with incidences of less than 5 percent). Among causes of non-infectious uveitis, multifocal choroiditis/punctate inner choroidopathy are the most common causes with 50 percent or more of cases developing an MNV. However, serpiginous choroiditis (10 to 25 percent) and Voyt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (9 to 15 percent) are also reported to have significant rates of MNV development.1,2 Untreated sarcoidosis very infrequently has also been reported as a cause of secondary MNVs.4,5 Treatment patterns vary, however, many providers treat with anti-VEGF with concurrent management of any underlying inflammation.

Tattoo-associated uveitis is an entity that remains poorly understood but likely exists on a shared spectrum with sarcoidosis.6 As such, imaging and clinical presentations can mimic sarcoidosis.7 Inflammation of the tattoo can be concurrent or precede an episode of uveitis, sometimes by many years. Patients often ignore or fail to appreciate the significance of their inflamed, bumpy or itchy tattoos, particularly in the context of other bothersome visual symptoms. In particular, the darker pigmented inks are more frequently associated with inflammation.6 Careful history and complete imaging are critical in making the diagnosis. Like sarcoidosis, patients often experience recurrent symptoms requiring chronic immunosuppression. Removal of the tattoos hasn’t been definitively shown to alter the disease course and is often not viable with large tattoos.

Bottom line

When TAU or sarcoidosis are suspected, a careful tattoo history is important. In addition, multimodal imaging should include ICG in addition to FA, as in some cases like the one reported, choroidal granulomas can be silent on fluorescein angiograms alone. While the definitive cause for the peripapillary MNV can’t be determined, treatment requires management of the underlying inciting disease entity. RS

References

1. Ozgonul C, et al. Management of peripapillary choroidal neovascular membrane in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol. 2019;39:4:451-457.

2. Wendel L, Lee AG, Boldt HC, Kardon RH, Wall M. Subretinal neovascular membrane in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:3:573-4.

3. Sathornsumetee B, Webb A, Hill DL, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Subretinal hemorrhage from a peripapillary choroidal neovascular membrane in papilledema caused by idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol. 2006;26:3:197-9.

4. Konidaris VE, Empeslidis T. Ranibizumab in choroidal neovascularisation associated with ocular sarcoidosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;14:bcr2013010288.

5. Matsou A, Dermenoudi M, Tzetzi D, Rotsos T, Makri O, Anastasopoulos E, Symeonidis C. Peripapillary choroidal neovascular membrane secondary to sarcoidosis-related panuveitis: Treatment with aflibercept and ranibizumab with a 50-month follow-up. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2021;12:12:1:186-192.

6. Kluger, N. Tattoo‐associated uveitis with or without systemic sarcoidosis: A comparative review of the literature. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2018;32:11:1852-1861.

7. Carvajal Bedoya G, Caplan L, Christopher KL, Reddy AK, Ifantides C. Tattoo granulomas with uveitis. Journal of Investigative Medicine High Impact Case Reports. 2020;8:2324709620975968.