|

|

Bios Dr. Hawn is an ophthalmology resident at UT Health San Antonio’s Long School of Medicine. Dr. Agarwal is a clinical professor at UT Health San Antonio. Dr. Thomas is a partner in vitreoretinal surgery and uveitis at Tennessee Retina in Nashville. Disclosures: No financial interests to disclose. |

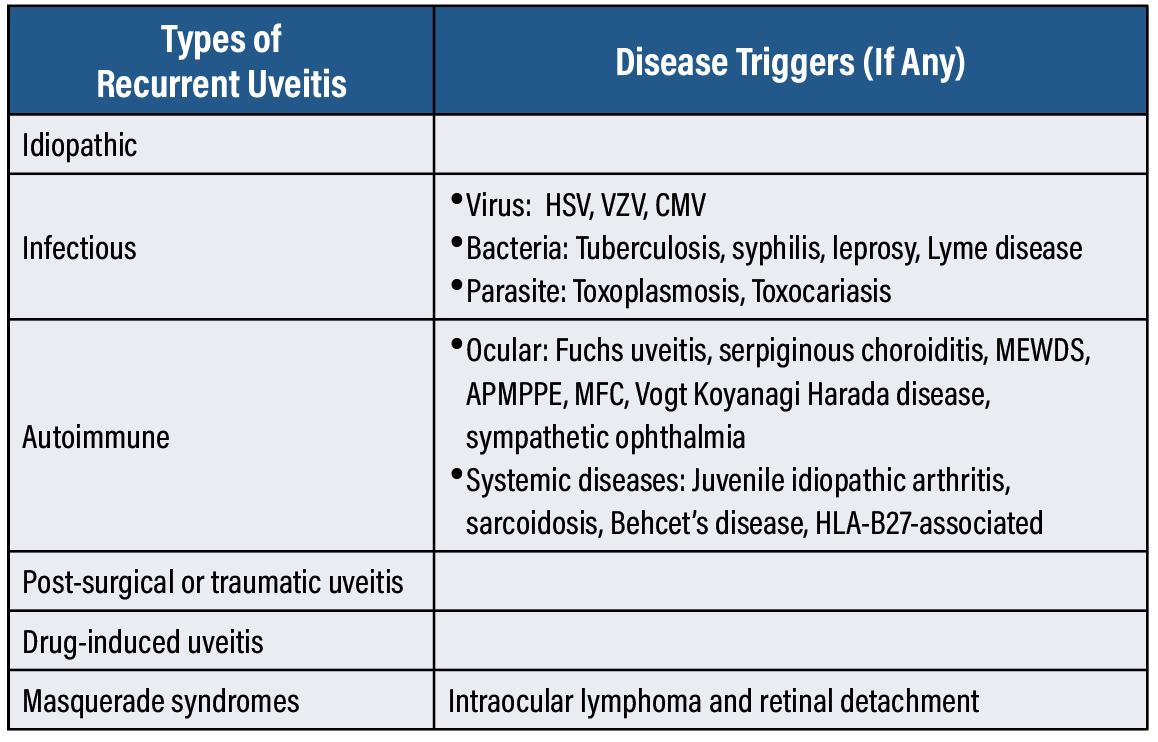

Recurrent uveitis remains a significant clinical challenge for ophthalmologists due to its complex presentation and management. As defined by the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group, recurrent uveitis involves repeated episodes of intraocular inflammation, each separated by at least three months of inactivity without ongoing treatment.1 Anterior uveitis is considered inactive when there are rare cells (fewer than one per field) on slit-lamp examination. However, there’s currently no standardized grading system for vitreous cells or a consensus on the definition of inactive vitritis.1

Here, we’ll review recurrent uveitis, outline how the disease develops and discuss how it’s managed.

Pathogenesis

Uveitis may occur in isolation or as part of a systemic disease. Recurrent episodes may be triggered by factors that reactivate latent infections, such as physical or emotional stress, ultraviolet light, trauma or concurrent infections.2 Nonetheless, identifiable triggers aren’t always present. Increased risk of recurrence has been associated with older age, Māori and Asian ethnicity, HLA-B27 positivity, inflammatory arthritis and viral etiologies.3 Here’s a rundown of possible causes of recurrent uveitis:

Infectious Causes

There are several infectious culprits to be aware of, including the following:

• Viral uveitis. Common viruses include herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus or cytomegalovirus.

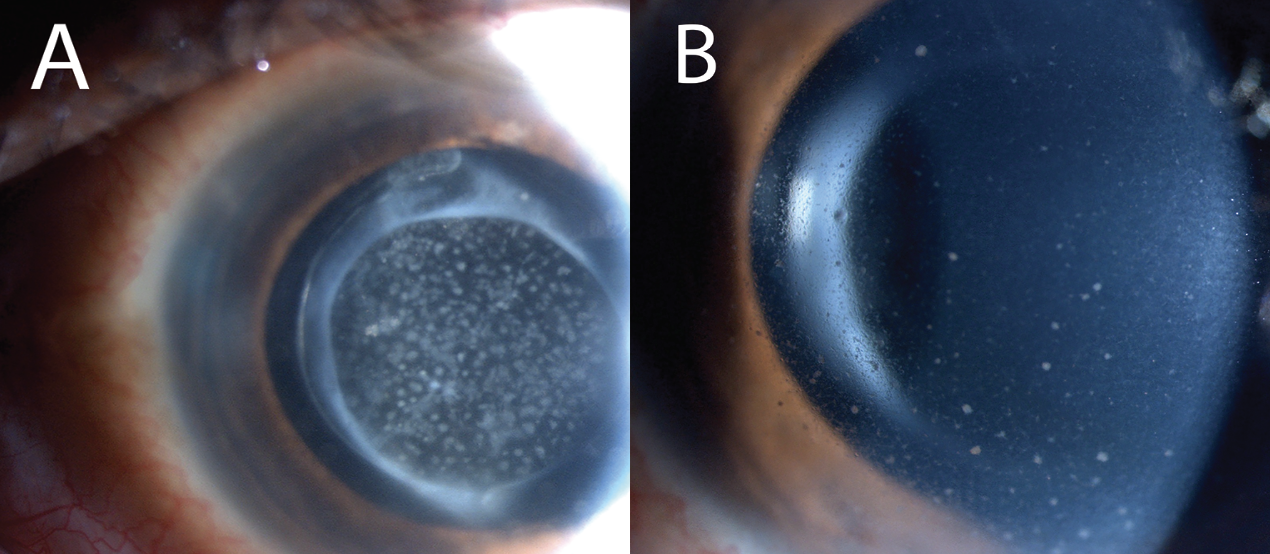

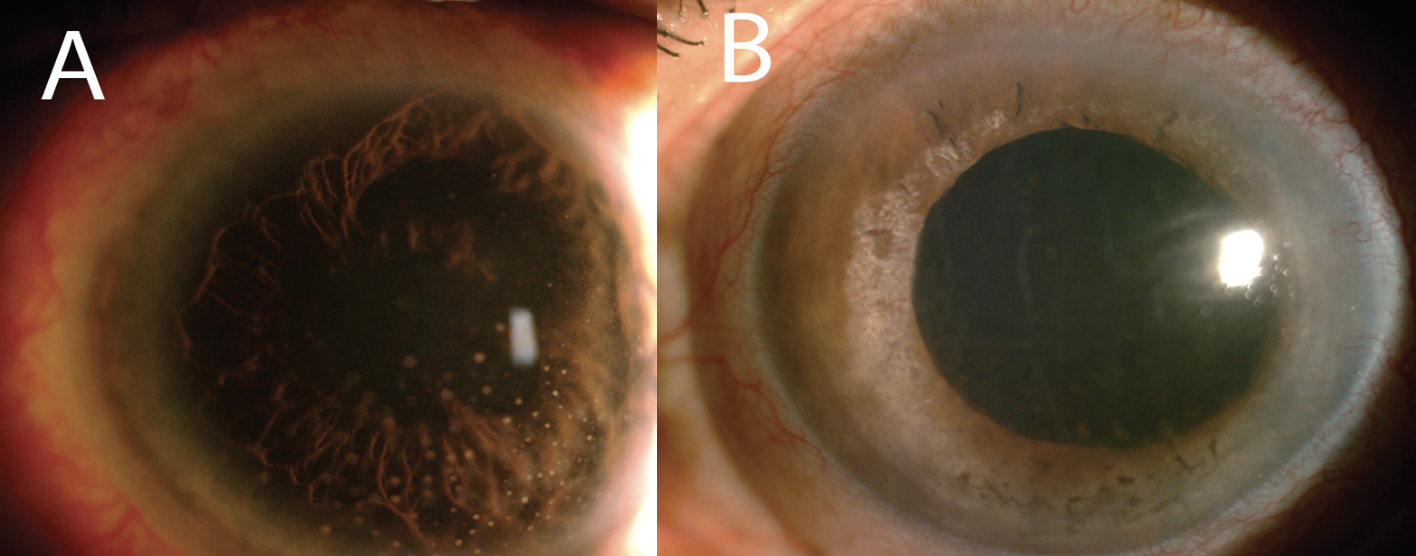

Anterior involvement presents with unilateral, elevated intraocular pressure, fine-to-medium keratic precipitates and varying anterior chamber inflammation (Figure 1). There may be concurrent epithelial keratitis, stromal keratitis and/or endotheliitis, depending on etiology. Additionally, HSV and VZV may present with posterior synechiae and/or sectoral iris atrophy (Figure 2).4

|

Posterior involvement is characterized by retinal infiltrates, vasculitis, macular edema, retinal pigment epithelium hyperplasia and/or peripheral retinal neovascularization.5 Acute retinal necrosis, predominantly affecting immunocompetent individuals, is most commonly associated VZV, less frequently HSV, and only rarely with CMV or Epstein-Barr virus. Clinically, ARN presents with vitritis, occlusive vasculitis, arteriolar thrombosis, peripheral necrotizing retinitis and, in some cases, optic neuritis. The retinitis typically manifests as deep, multifocal yellow-white lesions that coalesce in a concentric distribution within the peripheral retina, often sparing the macula. The distinct demarcation between necrotic and viable retina predisposes affected eyes to retinal breaks and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.

|

|

Figure 1. HSV-associated uveitis in a 35-year-old patient presenting with (A) diffuse, stellate, white keratic precipitates and (B) intraocular lens deposits. |

|

| Figure 2. (A) Conjunctival congestion and medium-sized white keratic precipitates in a patient with recurrent viral uveitis. (B) Diffuse iris atrophy, corneal edema and scattered pigment deposits on the endothelium CMV-associated anterior uveitis. |

• Tuberculosis. Can present as anterior, intermediate, posterior or panuveitis, with posterior uveitis being most common.6 Recurrences tend to manifest predominantly as either granulomatous or non-granulomatous anterior uveitis.1,2 The most frequent signs of posterior involvement include retinal vasculitis, choroiditis, choroidal tuberculoma, subretinal abscess and neuroretinitis.7,8

• Syphilis. Known as the “great masquerader,” syphilis has diverse manifestations, including anterior uveitis, vitritis, chorioretinitis, serous retinal detachment, retinal vasculitis and neuroretinitis.9 A hallmark presentation is acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis, which features large retinal whitening or solitary pale placoid lesions with central fading and coarse hyperpigmentation. These lesions may be accompanied by vitreous inflammation, hemorrhages, retinal vasculitis, optic disc edema and serous retinal or RPE detachment.10 A rarer form, syphilitic punctate inner retinitis, presents with superficial retinal precipitates, white spots in the inner retina and preretinal space, along with inner retinitis and arteriolitis.11

|

| Figure 3. Recurrent Toxoplasma retinochoroiditis with vasculitis. |

• Toxoplasmosis. This is the most common cause of posterior uveitis, characterized by focal necrotizing retinochoroiditis and significant vitritis (“headlight in the fog”). Reactivations typically occur adjacent to a chorioretinal scar (Figure 3). Other forms include retinal vasculitis and frosted branch angiitis.12

Autoimmune Causes

In addition to infection, autoimmune diseases such as the following can also result in recurrent uveitis:

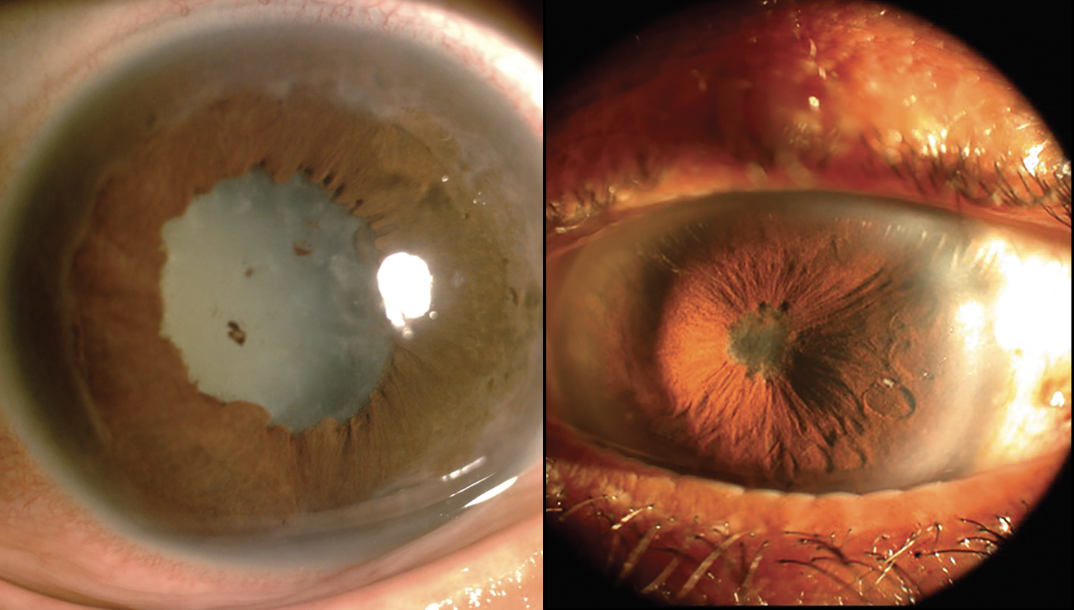

• HLA-B27-associated uveitis. This is the most common autoimmune uveitis, typically presenting in young patients as bilateral, non-granulomatous anterior uveitis. Recurrence or posterior involvement often suggests underlying systemic disease. HLA-B27 positivity is linked to more severe anterior chamber inflammation, which may extend into the anterior vitreous, and is frequently accompanied by fibrinous exudates, synechiae, iris bombe, cataract, secondary glaucoma and retinal vascular leakage (Figure 4).13,14 Due to its high recurrence rate, HLA-B27 testing is recommended in young patients with recurrent iridocyclitis, even in the absence of spondyloarthropathy symptoms.

|

| Figure 4. Chronic recurrent uveitis with peripheral anterior synechiae, posterior synechiae, cataract and iris bombé. |

• Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). This condition is commonly linked to asymptomatic chronic anterior uveitis. All children with non-infectious uveitis should be evaluated for joint swelling, stiffness or movement restriction. Due to its early onset and lack of symptoms, JIA-associated uveitis often leads to complications such as cataract, posterior synechiae, band keratopathy and cystoid macular edema.15 While topical steroids are first-line treatment, methotrexate is the preferred second-line agent, with other immunosuppressants used as needed. However, discontinuing therapy carries a high risk of relapse.16

• Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome. A bilateral granulomatous panuveitis marked by choroiditis, serous retinal detachment and optic nerve swelling. Recurrences often present as granulomatous anterior uveitis with mutton fat keratic precipitates, iris nodules and anterior chamber cells.

|

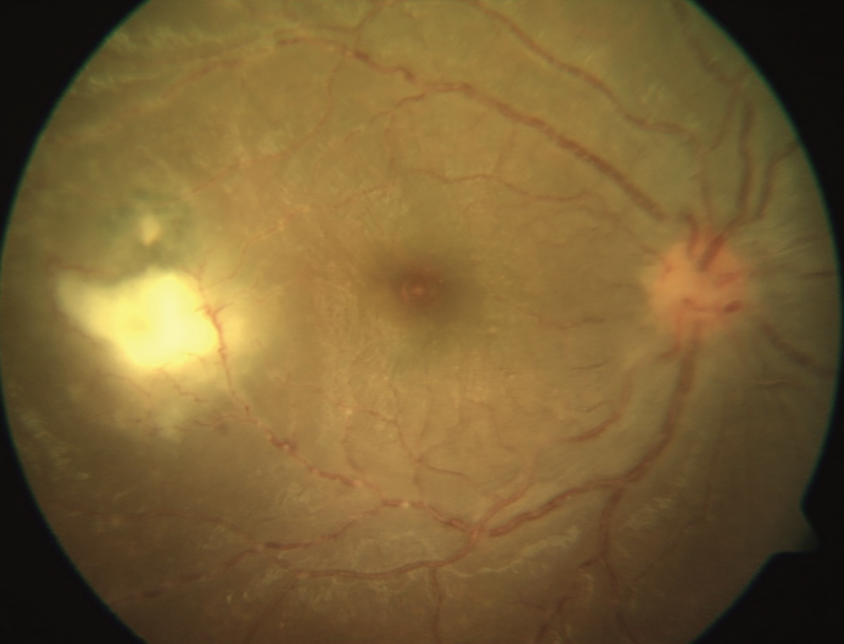

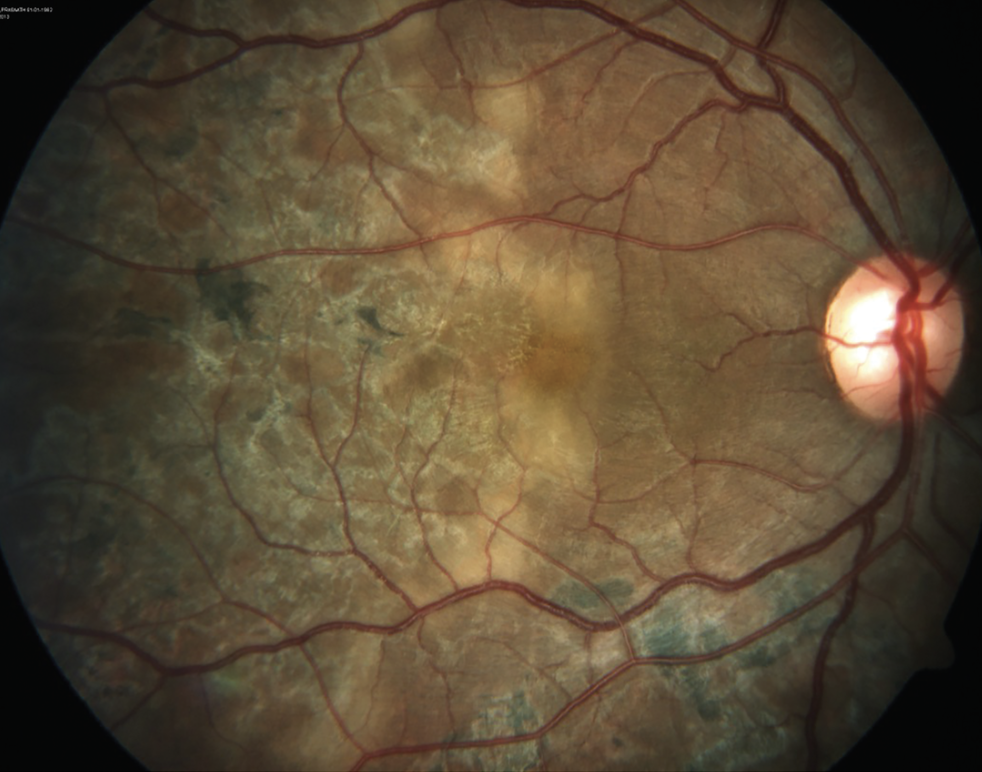

| Figure 5. Fundus photograph of the right eye showing reactivation of serpiginous choroiditis. |

• Serpiginous choroiditis. Rare, bilateral posterior uveitis characterized by multifocal lesions at varying stages of activity. Active lesions appear as gray or creamy yellow subretinal infiltrates, commonly originating in the peripapillary area and extending outward in an irregular, serpentine pattern. Within six to eight weeks—regardless of treatment—these lesions evolve into inactive areas of choriocapillaris and retinal pigment epithelium atrophy. Recurrences are frequent, occurring at variable intervals and often adjacent to prior atrophic scars (Figure 5). In chronic cases, findings may include widespread chorioretinal atrophy, subretinal fibrosis and dense pigment clumping of the RPE.

Medication- and therapy-associated uveitis17

Immune checkpoint inhibitors and kinase inhibitors (e.g., vemurafenib, dabrafenib, trametinib) have been linked to bilateral uveitis, which usually responds to steroids or cessation of the causative agent.

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors such as infliximab and adalimumab have also been associated with uveitis, along with various vaccines and biological therapies.

Other notable associations

There are a couple associations to be aware of, including:

• Tattoo-associated uveitis. Although not extensively studied, it has been reported to present as bilateral anterior or panuveitis. Some cases have included choroiditis, retinal vasculitis and serous retinal detachment.18,19 A thorough history correlating uveitic episodes with the timing of tattooing is essential for diagnosis.

• Masquerade syndromes. In patients with refractory or recurrent uveitis, especially the elderly, conditions such as intraocular lymphoma or endogenous endophthalmitis should be considered.

Management

Appropriate management of recurrent uveitis requires identifying any underlying etiology and monitoring for adequate treatment response.

• Investigations. Evaluation begins with a thorough personal and family history focusing on inflammatory, genetic and infectious diseases. A comprehensive eye exam should assess for keratic precipitates, anterior chamber inflammation, iris abnormalities, vitritis, vasculitis and chorioretinitis. Imaging techniques such as fluorescein angiography, indocyanine green angiography, optical coherence tomography and OCT angiography are essential for diagnosis and monitoring.

A single episode of anterior uveitis in the absence of systemic symptoms usually doesn’t require laboratory work. However, recurrent cases should prompt further testing for infectious or autoimmune causes. Intermediate, posterior and panuveitis require broader investigations due to their systemic associations and risk of vision loss. Recommended tests include complete blood count, metabolic panel, urinalysis, interferon-gamma release assay or chest X-ray, serum angiotensin-converting enzyme, syphilis serology and antibody testing for pathogens like Borrelia, Bartonella, Brucella and Toxoplasma. In select cases, retinal or chorioretinal biopsy, or fine-needle aspiration, may be needed. Aqueous or vitreous samples can be analyzed with PCR or cytology for viral infections or lymphoma. Posterior uveitis of unknown origin should be evaluated with syphilis serology and chest imaging to rule out sarcoidosis and tuberculosis.

• Treatment. Management is guided by the underlying cause and may include antivirals, antibiotics, corticosteroids and immunosuppressants. Topical corticosteroids are first-line for anterior uveitis, with difluprednate being the only topical agent effective for posterior segment involvement. Periocular or intraocular steroid injections or implants offer enhanced control for posterior uveitis. Systemic corticosteroids are reserved for severe, bilateral disease or when local therapy is unsuitable, such as in patients with glaucoma. Immunosuppressive therapy is indicated for bilateral disease, chronic inflammation, steroid resistance or significant functional impairment. Cycloplegics are used to relieve symptoms and prevent posterior synechiae. Treatment goals are to suppress inflammation, prevent recurrences and minimize treatment-related complications. Close, ongoing follow-up is crucial to monitor both disease progression and therapy side effects.

The prognosis of recurrent uveitis varies widely and is determined by the underlying etiology, the extent of ocular involvement, and how promptly treatment is initiated. Complications such as cataracts, macular edema, optic nerve damage and glaucoma can significantly affect visual outcomes. Due to the risk of relapse and potential for lasting vision loss, effective long-term management requires a tailored approach, regular monitoring and patient education to ensure early recognition and treatment of recurrences.

Bottom line

• Diagnostic evaluation is guided primarily by clinical history and examination findings.

• Recurrence rates vary significantly based on the underlying cause and individual patient risk factors.

• Treatment is tailored to the etiology and severity, using topical or systemic agents while balancing the risks of complications and medication side effects.

• Ongoing monitoring is essential to assess response and adjust therapy accordingly. RS

REFERENCES

1. Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT; Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the first international workshop. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;140;3:509-516.

2. O’Connor GR. Factors related to the initiation and recurrence of uveitis. XL Edward Jackson memorial lecture. Am J Ophthalmol 1983;96;5:577-599.

3. Brodie JT, Thotathil AZ, Jordan CA, Sims J, Niederer RL. Risk of recurrence in acute anterior uveitis. Ophthalmology 2024;131;11:1281-1289.

4. Chan NSW, Chee SP. Demystifying viral anterior uveitis: A review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2019;47;3:320-333.

5. Yoser SL, Forster DJ, Rao NA. Systemic viral infections and their retinal and choroidal manifestations. Surv Ophthalmol 1993;37;5:313-352.

6. Multani PK, Modi R, Basu S. Pattern of recurrent inflammation following anti-tubercular therapy for ocular tuberculosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2022;30;1:185-190.

7. Gupta A, Bansal R, Gupta V, et al. Ocular signs predictive of tubercular uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2010;149;4:562-570.

8. Gupta V, Gupta A, Rao NA. Intraocular tuberculosis: An update. Surv Ophthalmol 2007;52;6:561-587.

9. Tamesis RR, Foster CS. Ocular syphilis. Ophthalmology 1990;97;10:1281-1287.

10. Eandi CM, Neri P, Adelman RA, et al. Acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis: Report of a case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Retina 2012;32;9:1715-1722.

11. Wickremasinghe S, Ling C, Stawell R, et al. Syphilitic punctate inner retinitis in immunocompetent gay men. Ophthalmology 2009;116;6:1195-1200.

12. Goh EJH, Putera I, La Distia Nora R, et al. Ocular toxoplasmosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2023;31;7:1342-1361.

13. Wakefield D, Clarke D, McCluskey P. Recent developments in HLA B27 anterior uveitis. Front Immunol 2021;11.

14. Yang P, Wan W, Du L, et al. Clinical features of HLA-B27-positive acute anterior uveitis with or without ankylosing spondylitis in a Chinese cohort. Br J Ophthalmol 2018;102;2:215-219.

15. Sen ES, Ramanan AV. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Published online 2019.

16. Acharya NR, Ramanan AV, Coyne AB, et al; ADJUST Study Group. Stopping of adalimumab in juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis (ADJUST): a multicentre, double-masked, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2025;405;10475:303-313.

17. Moorthy RS, Moorthy MS, Cunningham ET. Drug-induced uveitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2018;29;6:588-603.

18. Kluger N. Tattoo-associated uveitis with or without systemic sarcoidosis: a comparative review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018;32;11:1852-1861.

19. Cunningham ET, Dunn JP, Smit DP, et al. Tattoo-associated uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2021;29;5:835-837.