|

Bios Dr. Fortenbach is an DISCLOSURES: The authors have no relevant disclosures. |

A community comprehensive ophthalmologist referred a 70-year-old woman to our clinic for a chief complaint of bilateral progressive worsening blurry vision. She reported that, although her vision had not been clear for years, it had significantly worsened over the past year in the left eye more so than in the right.

Her reading was most affected, and she reported visual distortion and missing letters. Her medical history was notable for hypothyroidism and interstitial cystitis, which previously required long term treatment with pentosan polysulfate (PPS, Elmiron, Janssen Pharmaceuticals). Notably, her urologist discontinued her PPS more than 18 months before the latest onset of symptoms. Her ocular history was noteworthy for dry age-related macular degeneration and cataract surgery in both eyes.

Pentosan polysulfate exposure

This patient suffered from years of severe interstitial cystitis complicated by Hunner lesions. Her condition was initially managed with PPS, but eventually controlled with intravesical heparin, lidocaine and buffer, as well as triamcinolone (Kenalog) injections and fulguration of the lesions. Her urologist started PPS for symptomatic management in 2011, which continued until 2021. Dosing ranged from ~100 mg to ~700 mg daily. Her estimated consumption was 200 mg daily from 2011 until 2016, and 300 mg twice daily until 2021, when she discontinued the medication due to visual symptoms. In total, this is an estimated consumption of about 1 kg over the full course of treatment.

Examination

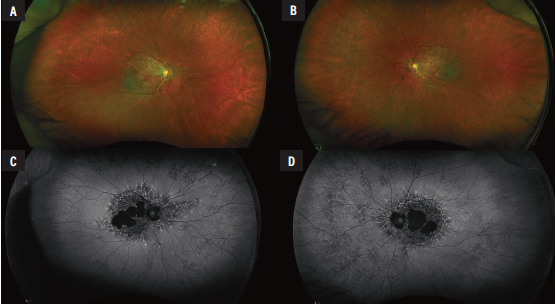

Examination showed uncorrected vision of 20/25 in the right eye and 20/40 in the left and no improvement with pinhole. Pupils were symmetric and no afferent pupillary defect was noted. Intraocular pressures were normal. Slit lamp examination was normal except for posterior chamber lenses in both eyes and a posterior vitreous detachment in the left. Dilated examination revealed peripheral reticular changes in the periphery of both eyes. The macula was notable for patches of atrophy with surrounding drusen in both eyes. (Figure 1A, B).

Work-up

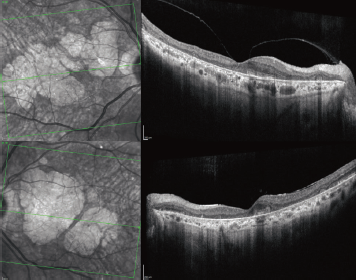

Fundus autofluorescence demonstrated dense peripapillary and central hypoautofluorescence surrounded by drusen and normal vessels (Figure 1 C, D). The periphery was notable for reticular changes with speckled hyper- and hypoautofluorescence. Optical coherence tomography showed an abnormal foveal contour and large areas of outer retinal atrophy adjacent to drusen deposits. No associated intraretinal or subretinal fluid was present (Figure 2).

Diagnosis and management

Given both the appearance of her fundus autofluorescence images, which are classic for PPS maculopathy, and significant cumulative exposure to PPS, we advised the patient to continue abstinence from PPS. We gave additional consideration to AMD as the diagnosis due to the substantial amount of drusen seen on exam.

We also reviewed the possibility that her PPS-associated maculopathy exacerbated her possible preexisting AMD. In the setting of her likely toxic maculopathy, we didn’t recommend newly approved injectable medications such as pegcetacoplan (Syfovre, Apellis Pharmaceuticals) and avacincaptad pegol (Izervay, Astellas Pharma). We continued the patient on AREDS2 vitamin supplements and home Amsler grid monitoring, and scheduled her for surveillance imaging.

|

|

Figure 1. A, B: Optos pseudocolor fundus photographyof the right and left eyes, respectively, demonstrated central geographic atrophy in both eyes as well as peripheral reticular changes. C,D: Fundus autofluorescence in the right and left eyes showed peripapillary and macular dense hypoautofluorescence surrounded by speckled hypo- and hyperautofluorescence, which was similarly seen in the retinal periphery. |

Potentially distinguishing signs

PPS was first prescribed for interstitial cystitis under the trade name Elmiron in the 1980s. The Food and Drug Administration approved it in 1996 and it remains the only approved oral medication for interstitial cystitis.1 Its usage reflects the high disease burden; it has been estimated that 3 to 6 percent of American women over age 18 years meet criteria for interstitial cystitis.2

The first case of PPS-associated pigmentary maculopathy was described in 2018 by Nieraj Jain, MD, of Emory Eye Center.3 This condition was most clearly defined by its distinctive pattern of hypo- and hyperautofluorescence within the posterior pole that may extend to the retinal periphery.

A key finding is the presence of a peripapillary halo of hypoautofluorescence, which isn’t commonly seen in hereditary maculopathies or AMD.4 This finding can clearly be seen in our patient.

OCT imaging generally demonstrates isolated thickening of or disruption in the interdigitation and ellipsoid zones. These areas of thickening are associated with hyperreflectance on near infrared imaging. In severe cases, loss of the retinal pigment epithelium and outer retina may be seen.5

Careful attention to these unique features may aid in distinguishing PPS-associated maculopathy from AMD. Unfortunately, the data suggest that PPS pigmentary maculopathy is underdiagnosed and is most likely mistaken as AMD or a pattern dystrophy.4,6

Higher dosage, higher risk

The risk and time of onset for PPS-associated pigmentary maculopathy remain areas of active research. What’s clear is that higher total drug dosage and duration is associated with an increased risk of developing ocular symptoms.

Cross-sectional studies of patients on PPS suggest that maculopathy prevalence is 12.7 percent in those who have taken 500 to 999 g of PPS, but rises to 41.7 percent of those who have taken more than 1.5 kg.7 The lowest amount of exposure was reported in a 44-year-old patient treated with 435 g of PPS over 36 months and who manifested symptoms 32 months after stopping treatment.8

Typically, once PPS maculopathy is diagnosed, it progresses symptomatically, as imaging will show in the months after the treatment stops.9 Although visual acuity is generally preserved until late in the disease progression, surveys suggest that the impact on activities of daily living, such as reading in dim conditions, is more pronounced than that which the Snellen chart can measure.10 Specifically, patients experience prolonged dark adaptation and difficulty seeing in low-luminance settings.

|

|

Figure 2. Optical coherence tomography of the right (top) and left eyes show geographic atrophy and dense drusenoid deposits. |

Bottom line and screening recommendations

Experts in PPS-associated pigmentary maculopathy suggest a comprehensive exam within six months after a patient starts PPS to establish a baseline, with repeat screening at three to five years with annual screening thereafter.1

Immediate cessation when indicated is strongly recommended because this disease currently has no treatment, is irreversible, and is progressive in nature. It’s important to discuss the risks of maculopathy with patients on PPS and to work with our urology colleagues to promptly identify those patients with maculopathy to limit potential vision loss. RS

References

1. Lindeke-Myers A, Hanif AM, Jain N. Pentosan polysulfate maculopathy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2022;67:83-96.

2. Berry SH, Elliott MN, Suttorp M, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis among adult females in the United States. J Urol. 2011;186:540-544.

3. Pearce WA, Chen R, Jain N. Pigmentary maculopathy associated with chronic exposure to pentosan polysulfate sodium. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:1793-1802.

4. Hanif AM, Armenti ST, Taylor SC, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of pentosan polysulfate sodium-associated maculopathy: A multicenter study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:1275-1282.

5. Dieu AC, Whittier SA, Domalpally A, et al. Redefining the spectrum of pentosan polysulfate retinopathy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2022;6:835-846.

6. Jain N, Li AL, Yu Y, VanderBeek BL. Association of macular disease with long-term use of pentosan polysulfate sodium: Findings from a US cohort. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104:1093-1097.

7. Vora RA, Patel AP, Melles R. Prevalence of maculopathy associated with long-term pentosan polysulfate therapy. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:835-836.

8. Barnett JM, Jain N. Potential new-onset clinically detectable pentosan polysulfate maculopathy years after drug cessation. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2022;16:724.

9. Shah R, Simonett JM, Lyons RJ, Rao RC, Pennesi ME, Jain N. Disease course in patients with pentosan polysulfate sodium-associated maculopathy after drug cessation. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138:894.

10. Lyons RJ, Brower J, Jain N. Visual Function in pentosan polysulfate sodium maculopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61:33.