|

Bios Dr. Felfeli is an ophthalmology resident at the University of Toronto. Dr. Rana is a second-year vitreoretinal surgery fellow and Dr. Kibe is an assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut. Disclosures: Dr. Felfeli and the authors report no relevant financial relationships. |

A 25-year-old woman who had an open globe repair after a motor vehicle accident was referred to the retina service for traumatic vitreous hemorrhage in the setting of a globe rupture.

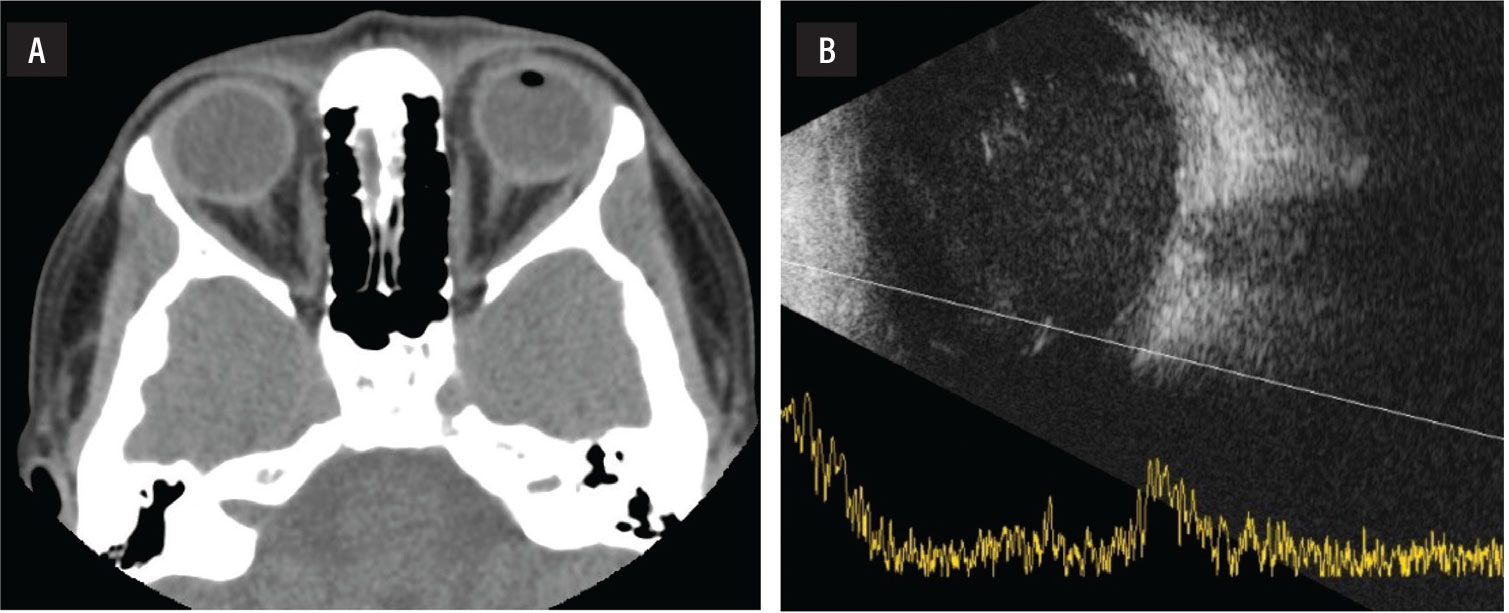

Before the globe repair, presenting vision was hand motion. A full-thickness corneal laceration with uveal prolapse had been noted. A noncontrast computed tomography scan of the orbits showed traumatic changes of the left globe, including intravitreal air and hemorrhage (Figure 1). An intraocular foreign body was not noted on the presenting CT scan.

Eight days after the globe repair, she was referred to the retina service. A B-scan showed dense vitreous hemorrhage.

Timing and planning

Upon evaluation, the patient’s vision remained HM, and intraocular pressure was 14 mmHg. The cornea was edematous, but the laceration was Seidel negative. A traumatic cataract was noted. A repeat B-scan was with vitreous hemorrhage, but an IOFB was not detected.

We maintained her on systemic and topical antibiotics. We elected to perform pars plana vitrectomy one week after presentation to give the cornea time to heal so that we would have adequate visualization for vitrectomy.

|

|

Figure 1. A) Noncontrast computed tomography orbits, interpreted as traumatic changes of the left globe, including intravitreal air and hemorrhage, did not detect an intraocular foreign body. B) Nor did a B-scan ultrasound of the affected eye show evidence of the IOFB. |

Performing the repair

We proceeded with a 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy, using a 6-mm infusion cannula because longer cannulas enable visualization of the cannula tip in the vitreous cavity in an eye with hemorrhage or other opacities.

|

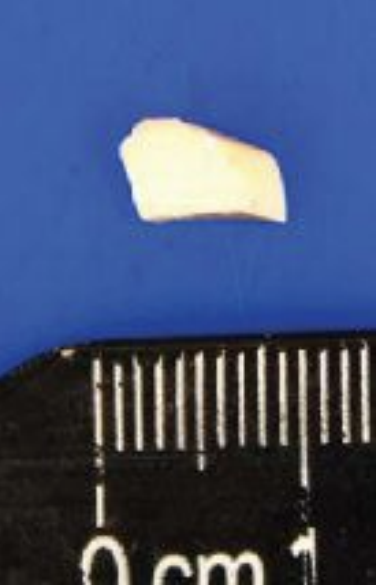

| Figure 2. The tan-white, nonmagnetic, plastic-like fragment measuring 9-x-4-x-3 mm intraocular foreign body removed during surgery. |

After visualizing the infusion cannula, we performed a pars plana lensectomy. We carefully cleared the dense, dehemoglobinized vitreous hemorrhage. As we cleared the vitreous hemorrhage and the posterior pole came into view, we noted an irregular, tan-white plastic IOFB on the macula (Figure 2).

We cleared the remaining vitreous attachments from the IOFB and carefully induced a posterior vitreous detachment. We slowly injected perfluoro-n-octane (PFO) to displace the IOFB and protect the macula. We also used PFO to elevate the IOFB as we prepared for removal.

PFO proved to be a useful adjunct to prevent further iatrogenic damage of the retina by the IOFB. Using foreign body forceps, we brought the irregular object into the anterior chamber and removed it through a large corneal incision. It measured 9 x 4 x 3 mm (Figure 3). On further inspection of the retina, we noted a superior retinal detachment and proceeded with retinal detachment repair with silicone oil tamponade.

|

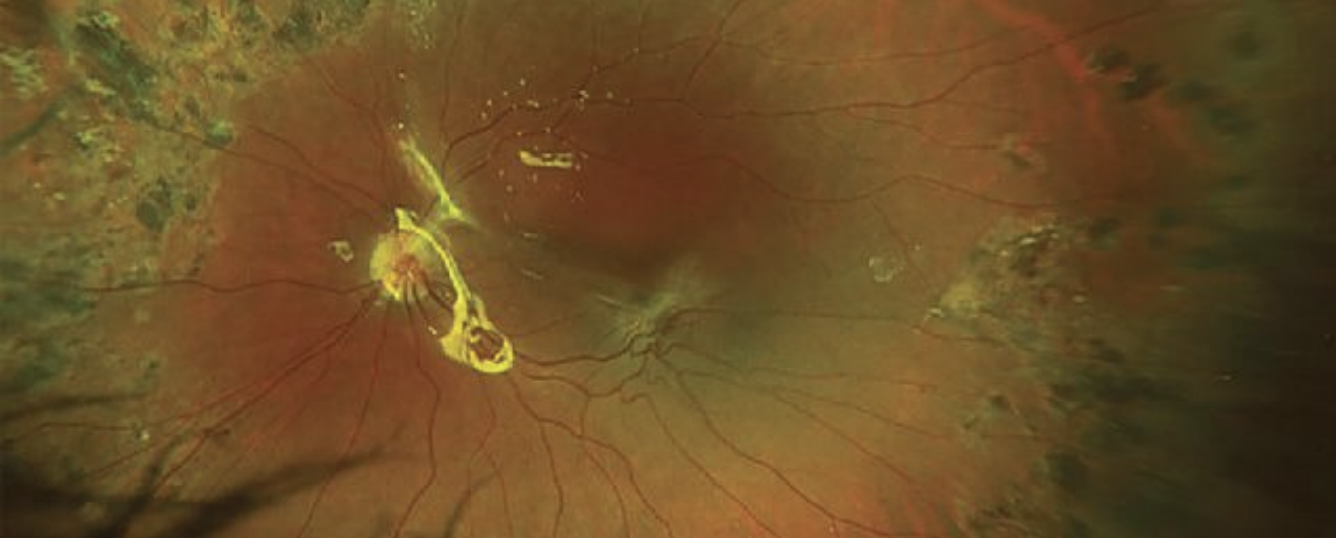

| Figure 3. Postoperatively, the retina remains flat and attached under oil. |

Bottom Line

An index of suspicion for possible IOFB is in order when examining a patient after open globe injury, even when preoperative imaging fails to detect a foreign body.1 This patient had an irregular plastic foreign body that eluded detection. Missed plastic intraocular foreign bodies have been reported,1,2 including an intravitreal plastic IOFB retained for 30 years.2 Early vitrectomy is the definitive management of post-trauma eyes with suspected foreign bodies. Consider PFO as a useful tool for retrieving IOFBs threatening the macula.3 RS

REFERENCES

1. Duker JS, Fischer DH. Occult plastic intraocular foreign body. Ophthalmic Surg. 1989;20:169-570.

2. Lin HC, Wang HZ, Lai YH. Occult plastic intravitreal foreign body retained for 30 years: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2006;22:529-533.

3. Ung C, Lains I, Papakostas TD, Rahmani S, Miller JB. Perfluorocarbon liquid-assisted intraocular foreign body removal. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:1099-1104.