|

Bios Dr. Felfeli is an ophthalmology resident at the University of Toronto. Dr. Zeydanli is an ophthalmologist in Ankara Retina Clinic, Ankara, Turkey. Dr. Ozdek is a professor of ophthalmology at Gazi University in Ankara. DISCLOSURES: The authors have no relevant disclosures. |

Retinal detachment in infants presents significant diagnostic and surgical challenges, especially when the underlying cause is elusive. Pediatric RD can result from various congenital or acquired factors.1,2 The distinct anatomical features of pediatric eyes, the tendency for late diagnosis, and frequent bilateral involvement make these cases more complex than adult detachments, requiring specialized approaches from diagnosis to management.1

Here, we discuss a case of a 3-month-old infant referred for bilateral RD with shallow elevation and no visible retinal breaks, initially leading to a misdiagnosis of exudative RD of unknown cause. Knobloch syndrome should be considered in babies or young children with high myopia, shallow RD and no apparent breaks, especially when there’s parental consanguinity and occipital skin defect or encephalocele.

Although rare, vitreoretinal interface abnormalities, including early-onset macular hole-related RD, are characteristic of Knobloch syndrome,3,4 prompting genetic testing.

In surgery for pediatric MH-RD due to Knobloch syndrome, innovative sealing materials such as amniotic membrane grafts and autologous Tenon’s capsule grafts are helpful for successful repair, particularly in young patients when internal limiting membrane peeling isn’t possible.

Hidden culprits in pediatric RDs

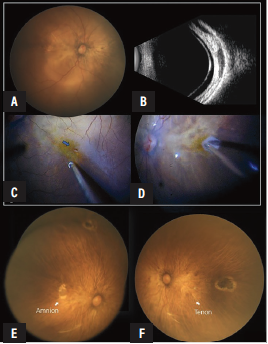

In this case, ocular examination revealed bilateral RD, with a highly myopic fundus and severe chorioretinal atrophy. Retinoscopy revealed myopic fundus reflex. Fluorescein angiography showed no signs of inflammation, and the absence of breaks shifted our suspicion toward an occult MH.

During vitrectomy, we discovered very small MHs, which were obscured by an operculum attached to the thickened and very tightly attached posterior hyaloid, confirming the diagnosis of Knobloch syndrome. The patient later underwent genetic testing and was found to have COL18A1 mutations.

Surgery in this case presented challenges because of an unusually strong posterior vitreous adhesion, a hallmark of Knobloch syndrome.5 In these cases, complete vitreous removal is often not possible without risking retinal breaks. However, careful dissection of the hyaloid over the macula and posterior staphyloma is critical. Bimanual techniques, assisted by perfluorocarbon liquid and repeated triamcinolone staining, are essential.

ILM peeling is generally not possible in very young pediatric patients because the ILM has not yet developed.5 To repair the MHs effectively, sealing materials are invaluable. We used an amniotic membrane graft for the right eye, while we used an autologous Tenon’s capsule graft as a seal in the left eye. One year after silicone oil removal, both retinas remained attached, and the infant was able to fixate and follow objects (Figure, below).

|

|

Preoperative fundus photography (A) and ultrasonography (B) show a shallow retinal detachment with high myopia and chorioretinal atrophy in the right eye. C) An occult macular hole became visible when the vitreous was gently pulled with a vitrector to lift its flap. D) The macular hole was sealed with an amniotic membrane graft. One-year postoperative images show attached retina with well-sealed amniotic membrane (E) and Tenon grafts (F) in right and left eyes, respectively. |

Tips and tricks for graft placement

The method for introducing grafts into the vitreous cavity depends on their size. Smaller grafts can be introduced through a valved trocar, while larger grafts may require the transient removal of the trocar to allow direct entry through the sclerotomy. Once inside the vitreous cavity, the amniotic membrane graft is gently manipulated under fluid or PFCL and transplanted through the MH or retinal break into the subretinal space, with the graft edges positioned under the edges of the defective area as much as possible, and with the chorion side facing the RPE.

In cases where the initial repair is at risk of failure, particularly in high-risk myopia, as in our case, a second layer of amniotic graft can be placed epiretinally (multilayer grafting). The orientation of the amniotic membrane graft is determined primarily by assessing the adhesiveness of the tissue using retinal forceps.6 However, for a Tenon’s capsule graft, orientation isn’t critical. RS

REFERENCES

1. Nuzzi R, Lavia C, Spinetta R. Paediatric retinal detachment: A review. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;10:1592.

2. Starr MR, Boucher N, Sharma C, et al. The state of pediatric retinal detachment surgery in the United States: A nationwide aggregated health record analysis. Retina. 2023;43:717-722.

3. Alzaben KA, Mousa A, Al-Abdi L, Alkuraya FS, Alsulaiman SM. Surgical outcomes of retinal detachment in Knobloch syndrome. Ophthalmol Retina. 2024;8:898-904.

4. Hull S, Arno G, Ku CA, et al. Molecular and clinical findings in patients with Knobloch syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:753.

5. Alsulaiman SM, Al-Abdullah AA, Alakeely A, et al. Macular hole–related retinal detachment in children with Knobloch syndrome. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4:498-503.

6. Caporossi T, De Angelis L, Pacini B, Tartaro R, Finocchio L, Barca F, et al. A human amniotic membrane plug to manage high myopic macular hole associated with retinal detachment. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020;98:e252–e256.